Lesson 3- Radiometry Basics

What You Will Learn

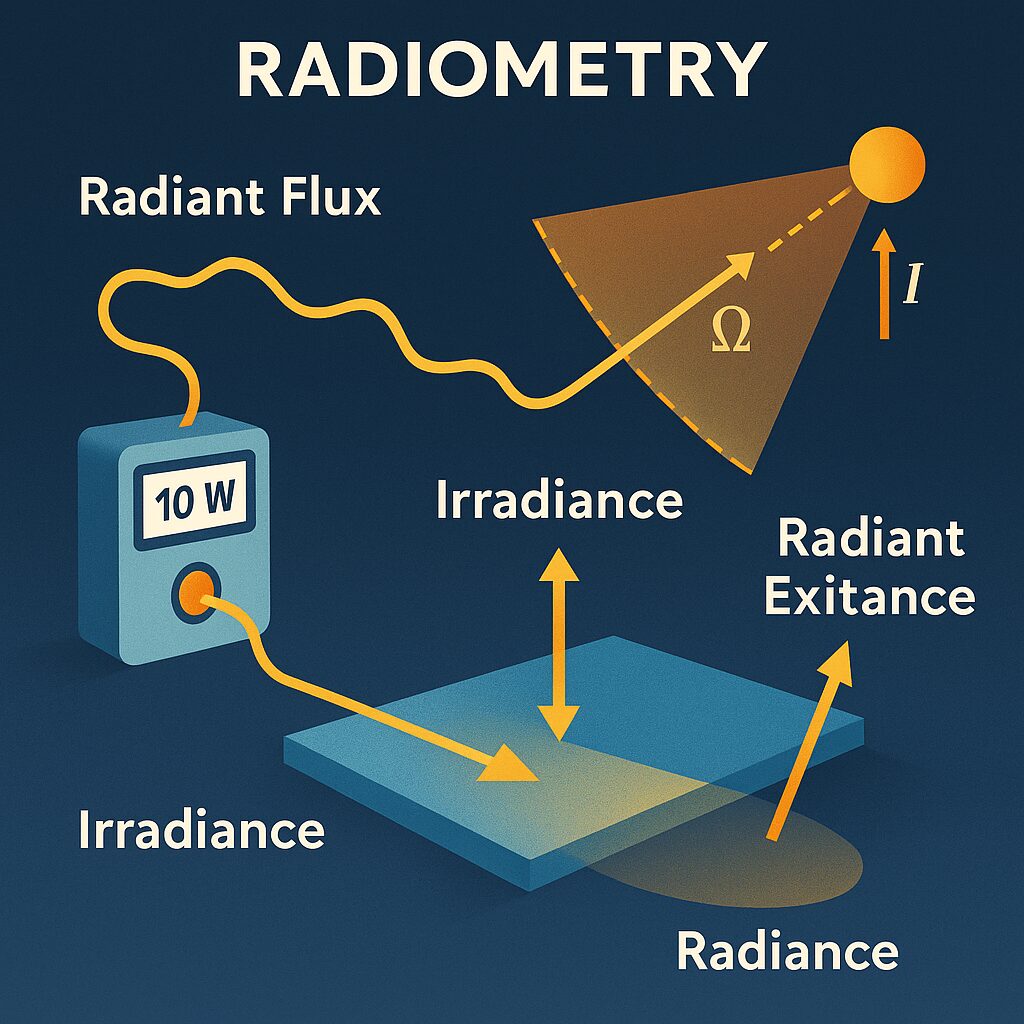

- Differentiate radiance, irradiance, flux, and intensity

- Apply units correctly (W/m²·sr vs W/m²)

- Connect radiometry to sensor calibration

- Relate optical power to geometry, solid angle, and collection efficiency

- Recognize when to use photometric versus radiometric quantities

Measuring Light

Radiometry is the physics-based framework for describing how light carries energy through space and how that energy is distributed over area, direction, and wavelength. Every optical measurement, whether made by a photodiode, CCD, or power meter, ultimately traces back to a radiometric quantity. Where photometry concerns human vision, radiometry concerns pure energy flow, independent of perception.

Radiometry is the physics-based framework for describing how light carries energy through space and how that energy is distributed over area, direction, and wavelength. Every optical measurement, whether made by a photodiode, CCD, or power meter, ultimately traces back to a radiometric quantity. Where photometry concerns human vision, radiometry concerns pure energy flow, independent of perception.

At its foundation, radiant flux (Φ) represents total optical power, measured in watts (W). It is the sum of all photons crossing a boundary per second, regardless of direction. From that total, we can derive more localized or directional measures.

Irradiance (E) is the power incident on a surface per unit area (W/m²).

Radiant exitance (M) is the power leaving a surface per unit area (also W/m²).

Intensity (I) is the power emitted by a point source per unit solid angle (W/sr).

Radiance (L) is the most complete descriptor, power per unit area per unit solid angle (W/m²·sr).

Radiance is particularly important because it remains constant along a ray in lossless media, a principle known as radiance invariance. In optical design and simulation, this property allows engineers to trace energy through lenses, coatings, and apertures without ambiguity.

When measuring light from a source or onto a detector, correct use of these terms determines whether results are physically valid. A detector’s signal is proportional to irradiance, not to flux alone. If the collection aperture or optical f-number changes, irradiance changes accordingly even if the source flux remains constant.

Units and Geometry

Radiometric units carry geometry within them. The steradian (sr) term, often overlooked, defines the solid angle that subtends an area on a sphere. One sr corresponds to the area of a unit sphere’s cap that covers one square meter at a one-meter radius.

When you measure a light source through an aperture or optical fiber, the captured power depends on both aperture area (A) and acceptance solid angle (Ω). Their product, A·Ω, is known as the etendue, a conserved quantity in optical systems that limits how much light can be transferred or focused. This concept governs everything from laser-beam coupling to telescope throughput. No optical system can increase radiance, it can only redistribute it. Understanding this conservation principle keeps design expectations realistic.

In practice, power meters read radiant flux (W). Imaging sensors measure irradiance (W/m²) across pixels. Calibrated integrating spheres account for total flux over 4π sr. Goniometers map intensity (W/sr) to characterize directional sources like LEDs.

Radiometry and Calibration

Accurate sensor calibration depends on disciplined radiometric bookkeeping. A camera’s pixel value is not brightness but an electrical response proportional to incident irradiance and exposure time. Calibration involves tracing this response back to a known radiance or irradiance standard under controlled geometry.

For example, in an optics manufacturing lab, a radiometer can calibrate a detector array used in interferometry or surface-scatter measurements. The lab maintains traceability to NIST standards, ensuring that each watt per square meter corresponds to an absolute, reproducible quantity. This traceability allows measurements of coatings, transmissivity, or laser power to remain valid across time and instruments.

Radiometry also bridges optical engineering and metrology. Coating thickness, absorption coefficient, and reflectivity are often inferred from ratios of measured irradiance. Without careful unit handling, those derived parameters can be meaningless. That is why every measurement notebook should record not just a number, but also its unit lineage, Φ, E, L, I, and Ω clearly identified.

Common Mistakes

Several recurring errors undermine radiometric data integrity.

- Mixing terms and units is common. Reporting intensity in W/m² is a contradiction, it omits the solid-angle dependence.

- Ignoring solid angle also causes problems. Many measurements assume 1 sr or isotropic emission without justification, leading to miscalculated power densities.

- Using photometric units for radiometric tasks produces incorrect results. Instruments reading in lumens or lux weight the spectrum according to human vision. For precision optics, these must be converted to watts or excluded entirely.

- Improper distance scaling is another issue. Intensity decreases with 1/r² for point sources, but irradiance on extended or focused sources can vary differently depending on beam geometry.

- Neglecting wavelength dependence can invalidate comparisons. Radiometric quantities can be spectrally integrated or spectral (per nm). Without specifying which, results are ambiguous.

When these pitfalls occur, downstream models, whether for coating efficiency, laser safety limits, or sensor gain, produce large errors. Maintaining strict radiometric discipline protects the reliability of every optical measurement and design decision.

Why Radiometry Matters in Optics Manufacturing

For AmeriCOM’s optics workforce, radiometry is not abstract theory, it governs real-world metrology. Every photodiode that verifies a coating uniformity map, every laser used in interferometric alignment, every calibrated lamp used for spectrophotometer testing, all operate within radiometric principles.

Technicians who understand radiance and irradiance can immediately detect when readings deviate from physical expectations. If doubling an aperture area does not double the measured flux, the issue might be vignetting or angular misalignment rather than sensor drift.

By internalizing these relationships, professionals ensure that data collected across shifts, instruments, and facilities remains traceable, consistent, and compliant with scientific and regulatory standards. Radiometry, therefore, is not just measurement science, it is the foundation of optical truth.