What You Will Learn

- Define refractive index, extinction coefficient, and Beer’s Law.

- Interpret attenuation and phase delay in glass and coatings.

- Model exponential absorption and energy loss.

- Relate transmission, reflection, and absorption to material composition

Refraction and Absorption

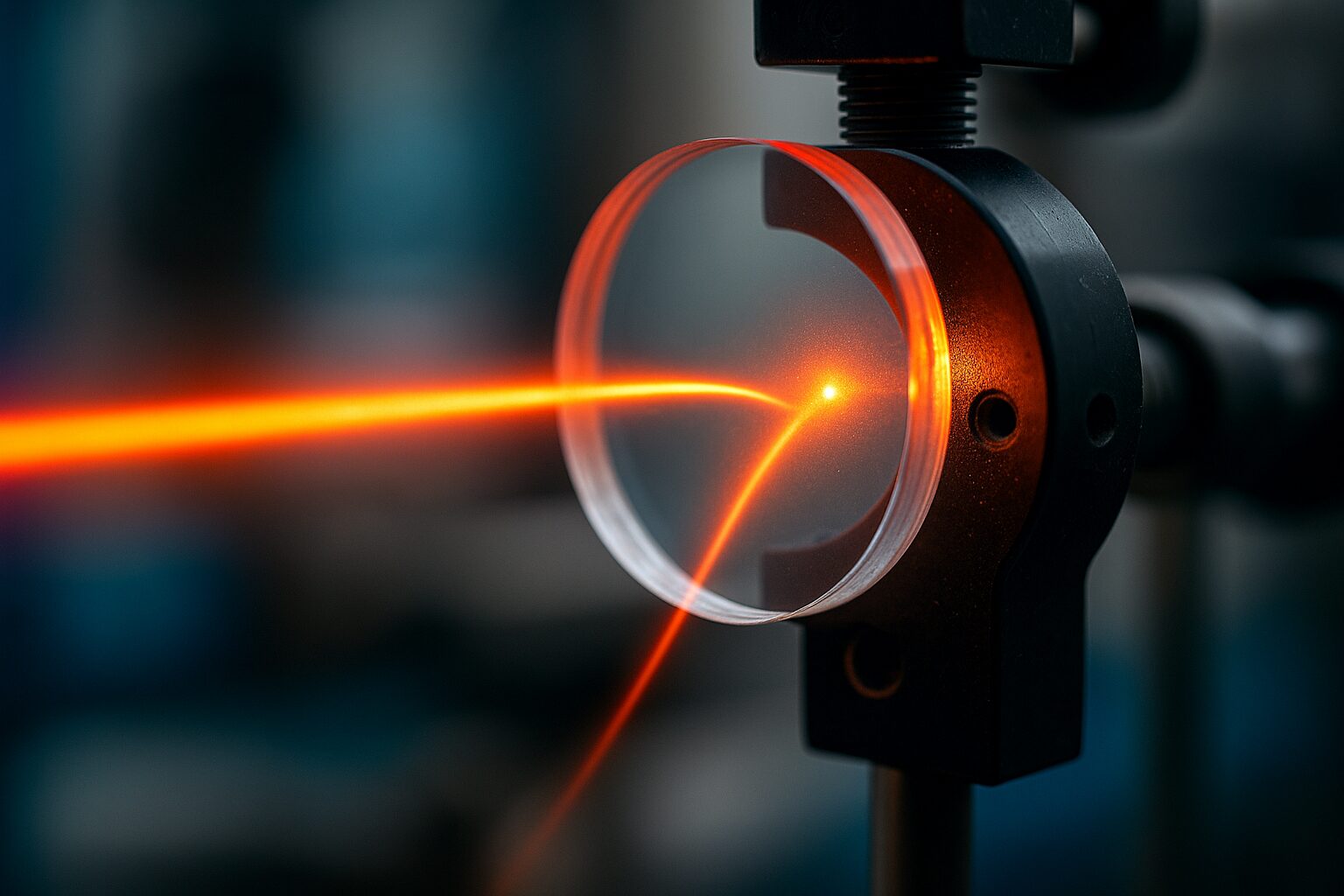

Light traveling through a transparent medium is governed by both its speed and its loss of energy. These two properties are expressed through the complex index of refraction, written as n = n′ + i k. The real part n′ determines how light bends and slows down as it enters a new material, while the imaginary part k describes how much of that light is absorbed and converted into other forms of energy such as heat. Together, they describe how electromagnetic waves propagate, refract, and fade as they pass through solids, liquids, or coatings.

Light traveling through a transparent medium is governed by both its speed and its loss of energy. These two properties are expressed through the complex index of refraction, written as n = n′ + i k. The real part n′ determines how light bends and slows down as it enters a new material, while the imaginary part k describes how much of that light is absorbed and converted into other forms of energy such as heat. Together, they describe how electromagnetic waves propagate, refract, and fade as they pass through solids, liquids, or coatings.

In optical engineering, these two parameters are essential to predicting how components will behave under illumination. A material with a high n′ bends light sharply, which is useful for focusing or imaging applications. A low k means the material is nearly lossless, allowing beams to maintain brightness and coherence through long optical paths. Conversely, materials with higher k values, such as metals or doped semiconductors, absorb light strongly and are chosen for filters, detectors, or controlled attenuation layers.

The interaction between light and matter also depends on wavelength. Even highly transparent materials like fused silica or BK7 glass exhibit measurable absorption at certain bands, typically in the ultraviolet and infrared regions where atomic and molecular resonances occur. Understanding this spectral dependence allows optical designers to select materials that minimize unwanted losses for specific operating wavelengths.

Beer’s Law in Practice

Beer’s Law, also known as the Beer–Lambert Law, provides the mathematical foundation for describing how light intensity decreases as it moves through an absorbing medium. It states that the transmitted intensity I is related to the incident intensity I₀ by the exponential relationship I = I₀ e⁻ᵅˡ, where α is the absorption coefficient and ℓ is the optical path length. The exponential form means that each additional unit of thickness removes the same fraction of the remaining light, not a constant amount. This creates a curve where transmission drops rapidly for large α or long paths, but remains nearly constant when α is small. Each horizontal bar is a different material. Bright yellow on the left is the incident beam, and the dimming toward the right shows how much light is transmitted after traveling a path length ℓ. All four materials obey the same exponential law I = I₀ e^{-αℓ}. The only thing that changes between rows is α, so you can directly see how stronger absorbers plunge toward zero transmission more quickly.

Beer–Lambert Law: Comparing Materials

In practice, Beer’s Law explains why tinted windows, optical coatings, or contaminated surfaces can dramatically reduce transmission even when they appear thin. A filter with an absorption coefficient twice as large as another does not simply absorb twice as much light, it absorbs an exponentially larger proportion as the beam travels through it. The same principle governs atmospheric attenuation, laser safety goggles, and the calibration of spectrophotometers used in quality control laboratories.

Experimentally, α can be determined by measuring transmission through samples of known thickness. From the slope of a plot of log (I₀/I) versus ℓ, technicians can extract the absorption coefficient and relate it to the extinction coefficient k through the expression α = 4πk/λ, where λ is the wavelength. This connection makes Beer’s Law not just an empirical relationship but a direct consequence of electromagnetic theory.

For coatings and precision optics, Beer’s Law is essential to designing anti-reflective or neutral-density layers that achieve target transmission values. Thin-film engineers adjust the composition and thickness so that absorption and interference effects balance properly. In metrology and interferometry, knowing how Beer’s Law modifies amplitude allows corrections for fringe contrast and helps separate true phase shifts from absorption-related intensity changes.

Practical Applications and Design Insight

Beer’s Law reveals that transparency is not absolute. Even the clearest optical glass slowly diminishes a beam’s power according to its internal structure, impurities, and surface treatments. By quantifying this process, optical professionals can predict performance, diagnose degradation, and ensure that each component in a system maintains the brightness and fidelity required for precision manufacturing and measurement.

Understanding n′, k, and Beer’s Law gives optical engineers the ability to evaluate losses before fabrication, select the right coatings for wavelength ranges, and maintain consistent output in optical instruments, from laser interferometers to high-precision polishing systems.